Architecture of Python Virtual Machine

Contents

Python virtual machine is the core part of this language. After compiling the original python code into Opcode(byte code), python VM will take the job left. Python will take every opcode from PyCodeObject.

Executing environment in Python VM

Actually, all the things that VM do is simulating what the OS do to excute a program.

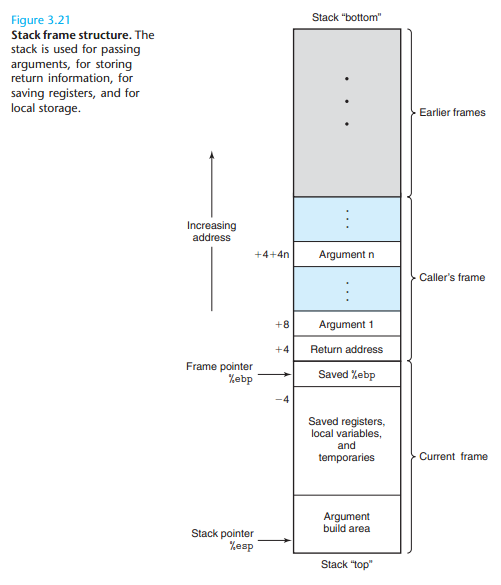

The figure over there show the representation of the model of stack-based machine.

If you are fimilary with system programming in C, it’s easy to understand the meaning of that figure.

But if you are an beginner with programming in C, you may try to finish the lab2( bomb ) in CSAPP. It will help beginner a lot to understand the mechanism of stack-based machine.

We know that all the static information about the program store in PyCodeObject. But what about the dynamic information when the program is running in the Python VM?

PyCodeObject can’t include the dynamic information and the environment where program is running.

|

|

You must know number in function f() and the variable which is not inside the block of function f() with the same name. That two variable are in different frame which means envrionment in running time.

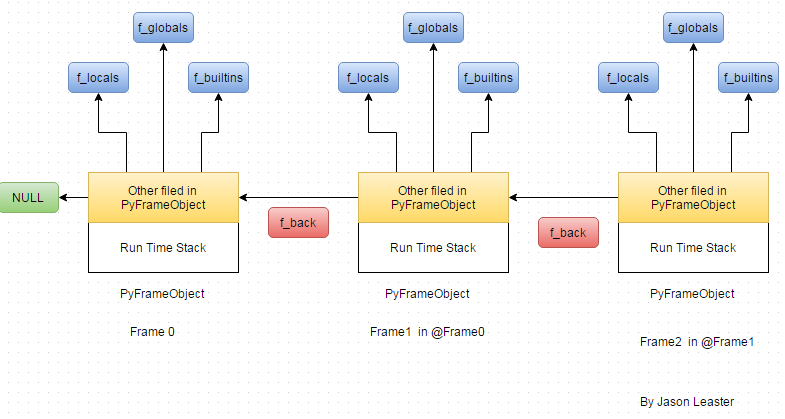

In Python, there is a class to describe the envrionment at running time – PyFrameObject. It’s a simulation of stack frame in x86 platform.

You noticed that PyFrameObject is a size-variable Python Object class. Because this class maintain a PyCodeObject and stack in different block have different size. So PyFrameObject can’t be a size fixed class.

|

|

This figure show the origanization of PyFrameObject like a single linked-list. f_back point to the previous frame. f_valuestack is something like ebp register in x86 and f_stacktop like the esp register.

How to create a new PyFrameObject? The answer is function PyFrame_New.

|

|

Luckly, we could access PyFrameObject in Python at running time.

|

|

Name, Scope and Namespace

We have knew the three different namespace – locals, globals and builtins.

In Python, there is a important basic structure – module.

More generally, every .py file is a module in Python. This concept help Python to divide namespace and reuse the program which have been writed.

Name is helpful to memory something which is not simple enough.

Assignment expression in Python have two things in common:

- Create a new object

- build a connection between that new object and a name

You may be familary with assignment like this x = 1. But expression likedef function(): and class A():, all these expression are also assignment expressions. What assignment to do is that build a connection between the object and name. It’s like a pair (name, object), (x, 1), (code, codeObject) and so on.

A namespace is corresponding with unique scope.

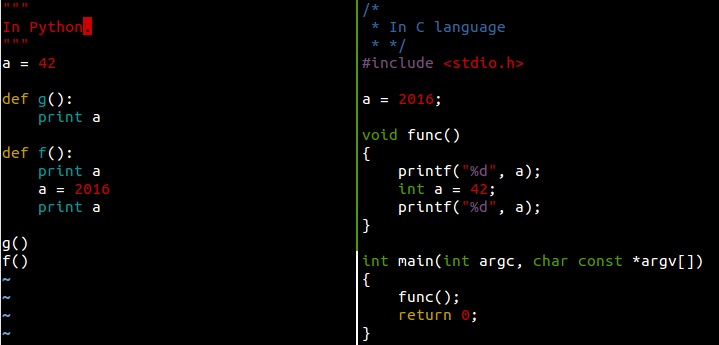

There is a comparasion between Python and C about namespace.

Just guess what would happend if you run these two program ?

The right side C program will run correctly but the left side Python program will run into exception for “local variable ‘a’ referenced before assignment”.

The reason is that no matter where the variable are decalred in the scope, all things in that scope can see that variable. But what is interesting is that the assignment expression are after the first print expression. When program run into the first print expression, the assginment are unfinished,

which means the local object haven’t created yet.

global keyword help programmer to declare a name which is in the global scope.

|

|

But you should know that once you declare a variable with global keyword, all thing happen to the variable in the local scope will influence that object in the global scope and change it’s value. After function f() finished, the value of a in global scope changed into 2016.

Runtime Architecture of Python VM

This function is the core part of virtual machine in Python. Once we get the opcode from PyFrameObject, the function PyEval_EvalFrameEx will process that opcode and run it.

|

|

Photo by QianNan Qu. In XiangTan, HuNan, China.

作者: Jason Leaster

来源: http://jasonleaster.github.io

链接: http://jasonleaster.github.io/2016/02/21/architecture-of-python-virtual-machine/

本文采用知识共享署名-非商业性使用 4.0 国际许可协议进行许可